We are on a mission to solve the biodiversity crisis by making nature restoration profitable for all.

Solving the biodiversity crisis is our purpose, making nature restoration profitable for all is our mission statement.

As we embark on this mission we wanted to provide some context around our purpose and mission which you may find useful.

Why is there a biodiversity crisis to solve?

The biodiversity or nature crisis is a statement recognising the accelerating rapid decline of the Earth’s natural world and we are worried we are going to soon cross a threshold where life can no longer sustain us humans.

I normally like to start talking about a subject very broadly and gradually hone in on the specifics so what better place to start as nearly as broad as it gets – 4.54 billion years ago – the forming of our planet, Earth.

This is a useful place to start because it is important to try and wrap our brains around the vast stretches of time over the Earth’s history which we break down into different geological time periods organised into eons, eras periods and epochs.

Life didn’t show up for nearly a billion years after the Earth first formed and it isn’t until around 540 million years ago that the rapid diversification of life forms began to occur, known as the Cambrian Explosion. We then had the dinosaurs roaming about from 230 million years ago to 66 million years ago when most of them went extinct.

The Cenozoic Era covers the last 66 million years where mammals evolved and diversified in the space left by the dinosaurs. We went through a number of Periods and Epochs of varying climatic conditions until we entered the Quaternary Period which is from 2.58 million years ago until today. This is the period we, homo sapiens, evolved and started to make our mark.

This was a period of revolving ice ages with large mammals like mammoths, mastodons and saber-toothed tigers knocking about until we hunted them to extinction. We then come to our latest Epochs, the Holocene and the Anthropocene. We entered the Holocene 11,700 years ago and human development really got rocking and rolling. We came out of the last ice age, the Holocene Epoch represents a time when the climate and environment was very accommodating to our development. It was nice and stable so that we were able to transition from hunter gatherers to settling down permanently in one place, growing crops based on the seasons and domesticating livestock.

Now during at some point during the Holocene we humans started to have increasingly big impact on life on Earth so much so that there is a growing scientific consensus that we have entered a new Epoch called the Anthropocene.

The start of the Anthropocene is still, interestingly, up for debate. Most scientists agree that the Anthropocene began in the 18th Century with the start of industrialisation. Here we got really good at harnessing energy in the form of fossil fuels to power the creation of things at a scale we had never been able to before. Others believe the Anthropocene began mid 20th Century inline with the acceleration of globalisation or as far back as the start of the 1600s when Europeans started to colonize the Americas.

The most important thing to recognise about the Anthropecene is not when it started, but that the development of our global society has impacted life on Earth so much that we have had our own Epoch named after us. This means that the people friendly conditions of the Holocene are no longer present across the planet. The next important question is, how much can we continue to influence the climate and environmental conditions we find ourselves in before they are no longer able to sustain our lives and development?

Planetary Boundaries

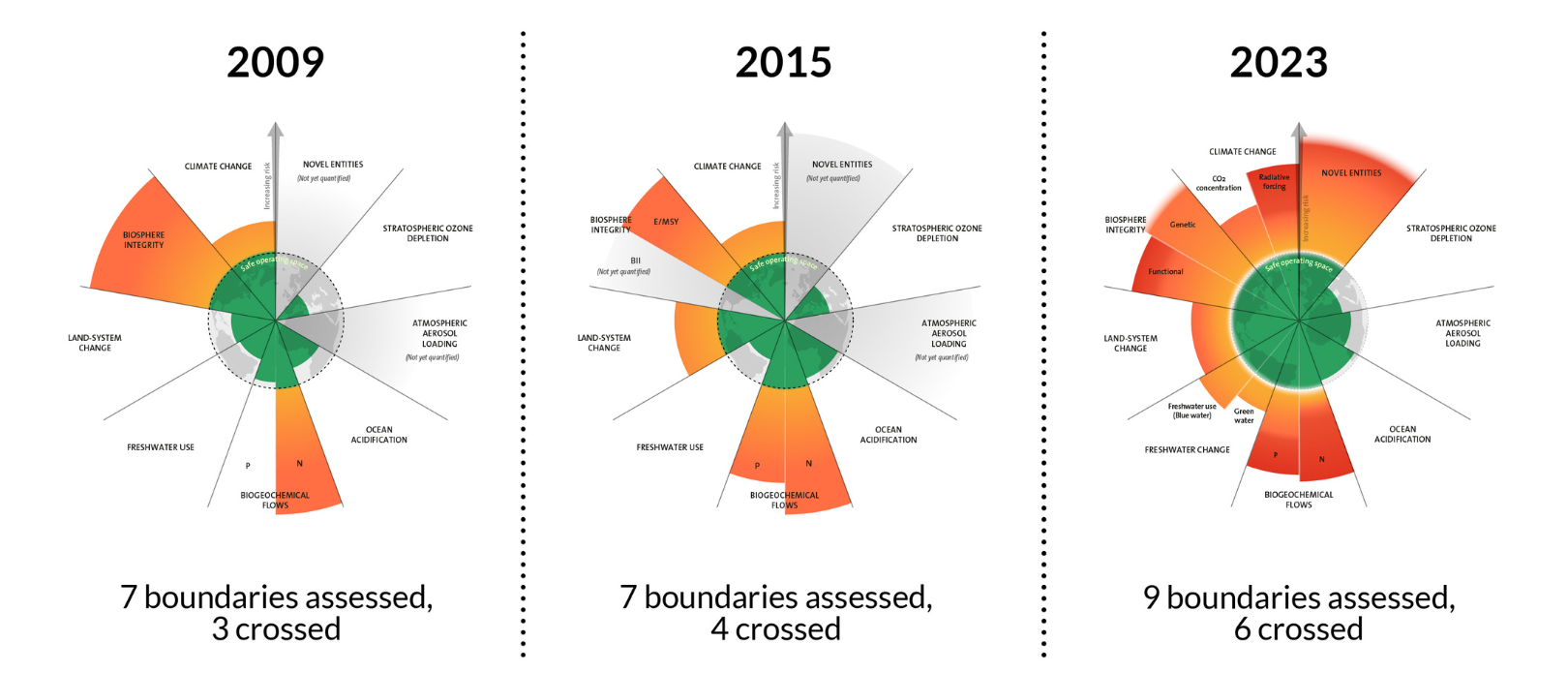

To answer this we can frame this within a set of 9 global environmental limits, first introduced in 2009 by Professor Johan Rockström, which we call planetary boundaries. As a global society we need to stay within these 9 limits to ensure the Earth remains stable enough to support us and our ambitions.

The limits can be seen in the diagram below – not wanting to stress anyone out too much but as you can see things aren’t looking particularly rosy at the moment.

Source: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

Since I started my undergraduate degree in Geography we have gone from 3 boundaries crossed to 6 boundaries crossed – that is in just 15 years!! Remember the time context at the start of this article? 15 years is 0.00000023% of 66 million years, the start of the Cenozoic Era and 0.001% of the Holocene (11,700 years). We can see that we have impacted Earth’s life systems so significantly in such a short space of time that the Earth is actually still reacting to this and we are still to experience the extent of these impacts, let alone reverse them!

Now all of the 9 boundaries are interrelated because they are driven by activities all carried out by the same species – us (joy).

At naturethrive and our mission in solving the nature crisis we are focusing directly on 2 boundaries, Biosphere Integrity and Land-system change. Transitioning to living within these specific boundaries will, however, also have positive impacts on all the other boundaries.

Biosphere Integrity is broken up into 2 areas, Genetic and Functional. Genetic diversity allows species to adapt to changing environments. The more genetically diverse a population, the better its chance of survival in the face of diseases, habitat changes, or climatic variations. Functional integrity refers to the variety and abundance of species that perform different ecological roles or functions within an ecosystem. This dimension focuses on how well ecosystems maintain their structure and processes (e.g., nutrient cycling, pollination, carbon sequestration) rather than just species richness.

Land-system change refers to the conversion of natural ecosystems (like forests, wetlands, and grasslands) into agricultural, urban, or industrial land. The safe planetary boundary is considered to be no more than 15% of Earth’s land surface converted to cropland – we are currently at 38% of cropland and pasture.

Now with this one we have to find a balance between providing enough food to feed what will soon be 9 billion people on the planet whilst transitioning back to living within planetary boundaries. In the UK specifically we have been converting natural ecosystems for hundreds of years and over the last 50 years we have been adopting large scale commercial agricultural practices to produce greater crop yields whilst simultaneously accelerating our negative impacts on Biosphere Integrity. This practice does not meet anyone’s definition of sustainability and we are estimated to have less than 100 harvests left using our current agricultural practices. The seeds of positive change have, however, recently started to germinate..

Why profitable and who are the stakeholders we mean by for all?

‘Profit’ is a word that may look out of place in a sentence discussing nature restoration and solving the biodiversity crisis. We understand the flaws of prioritising economic profit creation within our capitalist global system as it has driven unsustainable environmental degradation and societal wealth disparities. However Capitalism, warts and all, is here to stay and philanthropy combined with public sector financing will not fund the $700 billion/year global funding gap needed to solve the biodiversity crisis. We simply therefore have to make nature restoration profitable for the private sector and we are excited by the challenge and overwhelming opportunity this presents.

Who do we mean by ‘all’? Who are the stakeholders involved?

1. Nature. We define profitability from nature’s perspective as a measurable improvement in habitat conditions, species diversity and abundance. We aim to make the coming decades profitable for nature in a way that nature thrives.

2. Society. If, as a global society, we are to continue to exist and evolve to meet our full potential we need to connect with and value nature in a much greater way than we currently do. Ecosystem services are valued at more than $150 trillion/year and without them society very quickly collapses. Alignment between nature restoration and societal profit is therefore critical.

3. Landowners. Farmers and other landowners often feel proud to be custodians of their land. We need it to make economic sense for them to restore nature.

4. Organisations funding nature restoration. We need to move beyond basic philanthropy to provide organisations with a greater return on the investments they are looking to make in protecting and regenerating nature.

What is the aim of the game?

There are a couple of different global and national targets, both of which we fully support and are actively contributing to.

Nature Positive

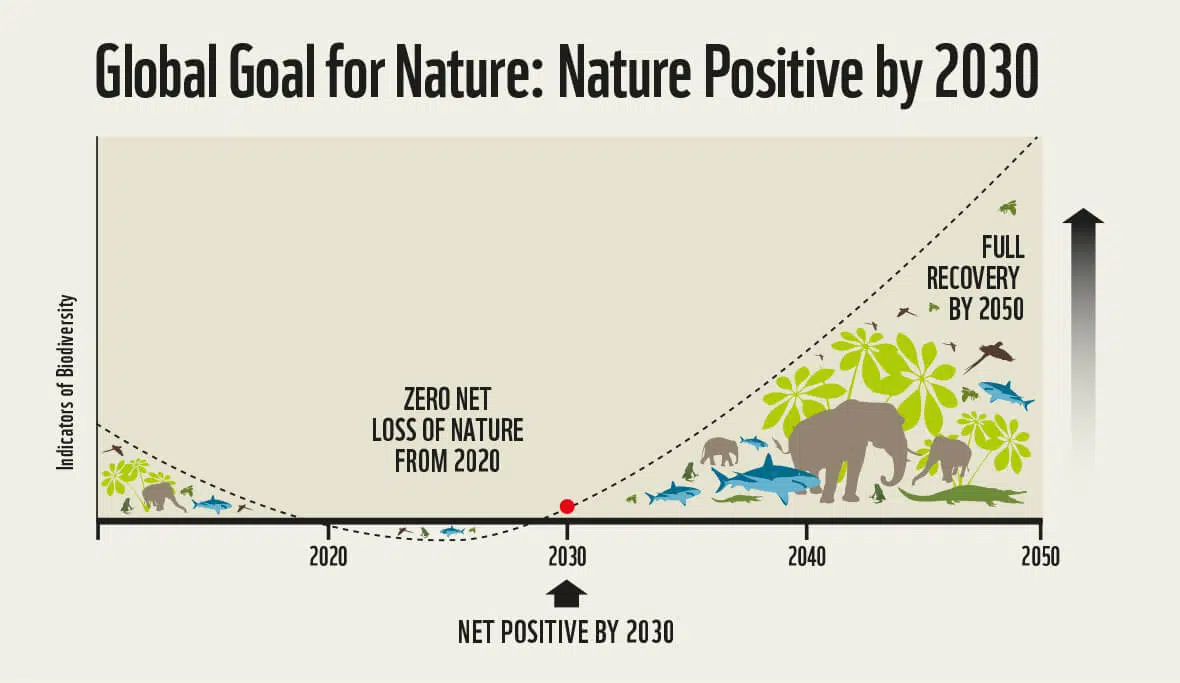

The Nature Positive Initiative was first launched in September 2023 which aims to promote the implementation of the Global Goal for Nature. This global goal’s target is to ‘Halt and Reverse Nature Loss by 2030 on a 2020 baseline, and achieve full recovery by 2050’.

In simple terms this goal is designed to ensure there is more nature in the world in 2030 compared to 2020 with momentum continuing to build on recovery after this.

Source: https://www.naturepositive.org/

There are a number of things that organisations in particular can do to support this goal, including:

- Assessing material impacts on nature

- Understanding dependencies on nature

- Risks and opportunities;

- Shift business strategy and models

- Commit to science-based targets for nature

- Report nature-related issues to investors and other stakeholders

- Transform by avoiding and reducing negative impacts

- Restoring, and regenerating nature

- Collaborating across land, seascapes and river basins

- Advocating to governments for policy ambition

naturethrive enables the direct contribution to restoring and regenerating nature and is in support of all of the other activities that organisations can undertake in contributing to the Nature Positive Initiative.

The Biodiversity Plan 30×30 Initiative

At the 2023 UN Biodiversity Conference the UK government was one of those countries that committed to the 30×30 target. There are already a number of mechanisms like Natura 2000 sites, National Nature Reserves (NNRs), and broadleaved woodlands classified as Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs).

These mechanisms will not be enough and we are super passionate about the role of private sector capital in contributing to not only the protection of nature but it’s restoration in a way that is profitable for all.

Biodiversity Net Gain

Boris Johnson, for all his faults, actually championed the civil servants at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) during his tenure to come up with a legislative mechanism for catalysing the flow of private capital into nature restoration to bridge the £56 billion funding gap over the next 10 years or so needed to help protect and restore 30% of the UK’s land and sea by 2030.

After a number of years in development, BNG went live in February 2024 under Schedule 7A of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as inserted by Schedule 14 of the Environment Act 2021).

BNG focusses specifically on building developments and is designed to ensure that habitats for wildlife are left in a measurably better state than they were before the development. Developers must deliver a BNG of a minimum of 10%.

To achieve a 10% net gain in biodiversity, developers can use a combination of on-site and off-site measures.

There are a number of cost implications to consider when selecting what onsite and offsite initiatives to introduce to ensure compliance.

Onsite Measures

Includes all land within the projects red line boundary with activities including:

- Retaining and enhancing habitats

- Planting new amenities and structural landscapes

- Creating extensive green roofs

Offsite Measures

Includes all land outside of the project’s red line boundary, regardless of ownership with activities including:

- Creating or enhancing habitats on private land adjacent to the red line boundary of the development

- Purchasing offsite BNG units developed on other privately owned land

- Purchasing offsite BNG units from third party providers who have created Habitat Banks as part of private offsite BNG market

- Procurement statutory biodiversity credits from the Government

We won’t go into any more detail behind how all this works within this article except to say that what makes BNG different from say, carbon credits, is that a land owner enters a legal agreement to lock in the nature restoration project for a minimum of 30 years which is audited and monitored by either the Local Planning Authority or Responsible Body to ensure the Habitat Management Plan is being implemented. This makes this super credible and has a huge amount of potential.

The other thing to highlight, linked to our mission, is this is currently the most profitable mechanism for landowners in England to restore and protect nature on their land which is super exciting.

What next?

We are loving what we are doing and are having daily conversations with people who are passionate about the role everyone can play in helping make nature thrive again. Our values around courage, support, optimism and passion will shape the decisions we make going forward and we welcome anyone who wants to be part of the journey with us.

References

CIRIA, CIEEM, IEMA (2019). “Biodiversity Net Gain: Good Practice Principles for Development.”

Dalrymple, G. Brent. The Age of the Earth. Stanford University Press, 1991.

Defra (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs): Publications and guidelines on Biodiversity Net Gain practices in the UK.

Ellis, E. C., Goldewijk, K. K., Siebert, S., Lightman, D., & Ramankutty, N. (2010). “Anthropogenic transformation of the biomes, 1700 to 2000.” Global Ecology and Biogeography.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations): Reports and data on global land use and agriculture.

International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS): Updates on geological time scales and official epoch definitions.

IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services): Global assessment reports on biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005): Reports on ecosystem services and biodiversity.

Rockström, Johan et al. “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” Nature 461, 472–475 (2009).

Stanley, Steven M. Earth System History. W.H. Freeman, 2014.

Schopf, J. William. Cradle of Life: The Discovery of Earth’s Earliest Fossils. Princeton University Press, 1999.

Steffen, Will et al. “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet.” Science, 2015.

Stockholm Resilience Centre, which provides updates and research on the planetary boundaries framework: Stockholm Resilience Centre.

The Biodiversity Metric 4.0 (by Natural England): A tool for measuring biodiversity value and planning net gain in development.

UK Environment Act 2021: Legal framework that includes mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain for developments.

World Bank: Land use data in global development indicators.